THE X-FACTORIES

13th March 2024

Three of ROX’s favourite ‘manufacture’ watch brands harbour a singular in-house nous not seen anywhere this side of the Jura mountains. Words by Alex Doak.

They might all still be perched on the rolling slopes of the Jura mountains, surrounded by clanking, cud-chewing dairy cows, but these days the self-contained Swiss watch ’manufacture’ is a particularly different prospect to your imagining of hunched Geppetto types with smocks and tweezers.

They’re all there because of a bizarre turn of industrial and religious events, with snow-enforced job diversification thrown in. But regardless of Calvinist puritanism, Huguenot persecution by Louis XIV and winterised cheesemakers, the serene environs continue to benefit Switzerland’s finest watchmakers and their timeworn craft.

Not only that, but afford the headspace to innovate: with process and materials, if not the anachronism that continues to be the tick-tocking mechanics inside their creations.

Whether it’s Hublot’s sprawling campus near Lake Geneva, Bulgari’s bucolic Saignelégier facility on the French border, or Tudor’s gleaming new facility in ‘Watch Valley’ down the road from Zenith and TAG Heuer, any visitor starting their tour on ground floor will be greeted by a staggering battery of computer-numerical-control (CNC) milling machines. In five, seven or even eleven axes, their robotic drilling bits are transforming raw bars of brass and steel into intricately sculpted baseplates and bridges.

Upstairs, the traditional rows of labcoated watchmakers are now interwoven by a fully automated Scalextric-like conveyor system. Each part-complete movement assembly arrives at its next workstation riding colour-coded ‘cars’, fed by stacked magazines. Man and machine in eerie concert, aided by technology – appropriately enough – from blood-sample analysis labs.

It’s an autonomy that has seen warranties extend from two years to a standard five. But with an unexpected upshot: leapfrogs in niche, in-house specialities: quality control, testing, materials innovation, ad nauseam. It distinguishes ‘maker’ brands with a particular ‘thing’, sure. But crucially, keeps the barside conversations fresh for watchnerds like us, and 21st-century mechanical watchmaking even fresher.

CRYSTAL METHODS

From sapphire to rubber and gold, Hublot is THE Swiss alchemist.

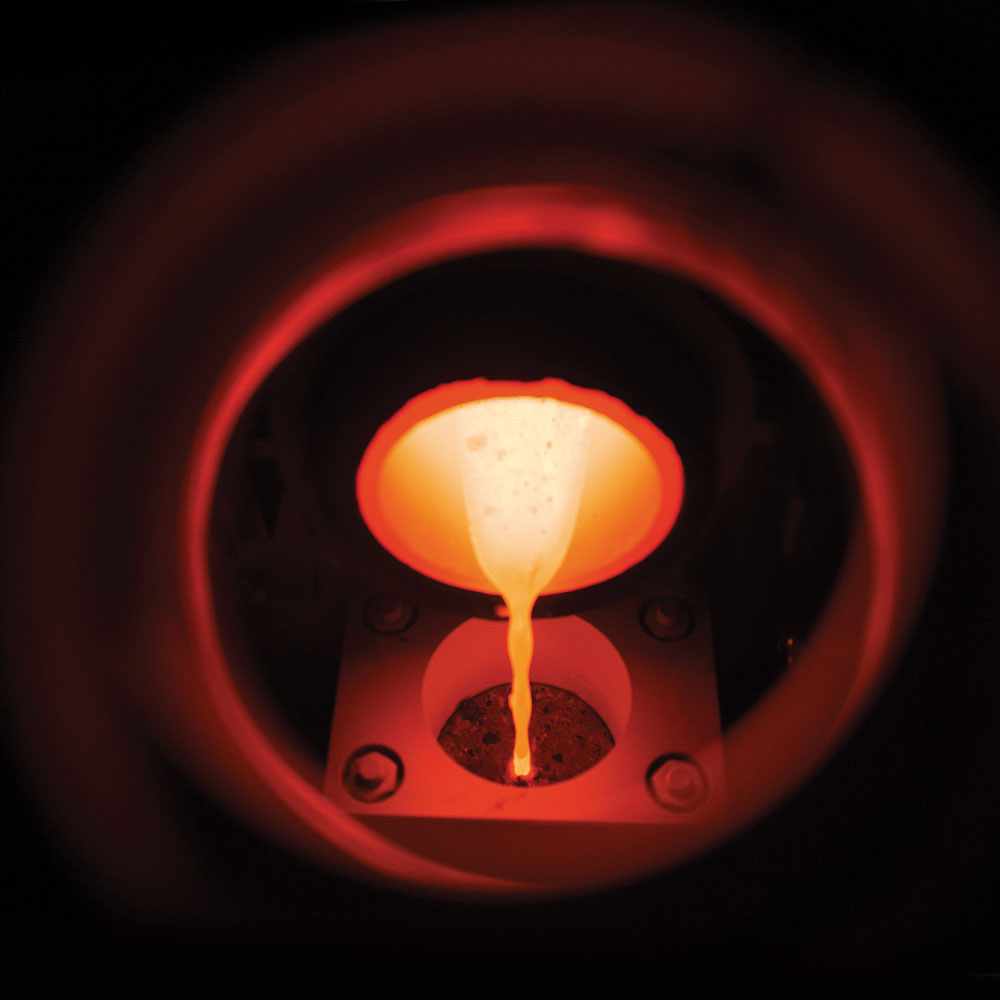

Lausanne’s École Polytechnique Fédérale (EPFL) had a tough brief almost 15 years ago: develop an 18-carat gold that wouldn’t scratch. Their hot young buck Senad Hasanovic – who went on to set up an actual ‘metallurgy and materials’ division chez Hublot HQ – came up with ‘Magic Gold’.

It was made by fusing 24-carat gold with a porous ceramic substrate under tremendous pressure and temperature, to give a scratch resistance of 1,000 Vickers. Normal 18-carat gold is 400 Vickers, by comparison.

“Why do we go to these lengths?” he told ROX at the time. “It’s because, as a young brand, we can’t talk about heritage. So materials are the thing that differentiates us. And now we have the foundry in-house, the cool thing is that Hublot can continue to experiment.”

By watchmaking standards Hublot is indeed very young, founded in 1980 by the scion of the Italian Binda Group dynasty, best known for making Breil watches. But as unique as Hublot’s eponymous porthole-shaped case was, Carlo Crocco’s ensuing three years of R&D was primarily occupied with what his gold vessel was conveyed by, come launch in 1983.

Crocco was an avid sailor, and he was unsatisfied with the metal bracelets and leather straps solely available at the time. He wanted to create a watch that looked as good with a suit and tie as it did on the deck of a sailboat. A latex compound, most commonly sourced from the Pará tree was the perfect mix of stretch, water resistance and pristine durability – known by its French name ‘caoutchouc’.

But in the late 1970s no one knew how to work natural rubber to watchmaking’s standards of UV, dust, chemical and wear-resistance – already achieved with purely synthetic rubber by strapmakers like Omega’s go-to, Isofrane. So Crocco looked to tyre producers to create the exact mix, reinforced by an inner steel blade for thinness, flexibility and resilience – the genius touch was to add a vanilla scent to the mix, masking the slight acrid smell of the natural material.

Where is Hublot’s fire now burning the brightest? Sapphire. Borderline alchemists, and seemingly with a closely guarded process that keeps things bafflingly affordable (at least by comparison to other crystal-cased watches) the Nyon brand continues to describe a rainbow of rocksolid (literally rocksolid) aluminium oxide Big Bang watches in unprecedented colours. Inclusion and imperfection-free, these 2,000ºC-fused, 3D jigsaws of components are all agonisingly machined to water-tight tolerances.

If Willy Wonka was a watchmaker, he’d work at Hublot.

HUBLOT watches are available online and at ROX Glasgow, Edinburgh, Newcastle and Liverpool.

DOCTOR OCTAGON

Fashioning the 110 facets of Bulgari’s single-block ‘Octo’ don’t come easy.

The village of Saignelégier is as sleepy a Swiss backwater as you’re likely to find. The main business appears to be horses, with a sign welcoming you to “the cradle of the Franches-Montagnes” – Switzerland’s most celebrated breed, examples of which meander about the surrounding pastures. Paying little mind to their neighbour, one of the most noble names in luxury.

Opulent, monumentally Roman, magisterial and fully Liz Taylor-endorsed Bulgari has wrought a quiet revolution in Swiss watchmaking over the past two decades. The brand’s early-Noughties acquisition of horological hothouses Gérald Genta and Daniel Roth ensured there was no shortage of ingenuity on the tourbillon or minute repeater front. But how to channel Bulgari’s inherent Italian flair in concert?

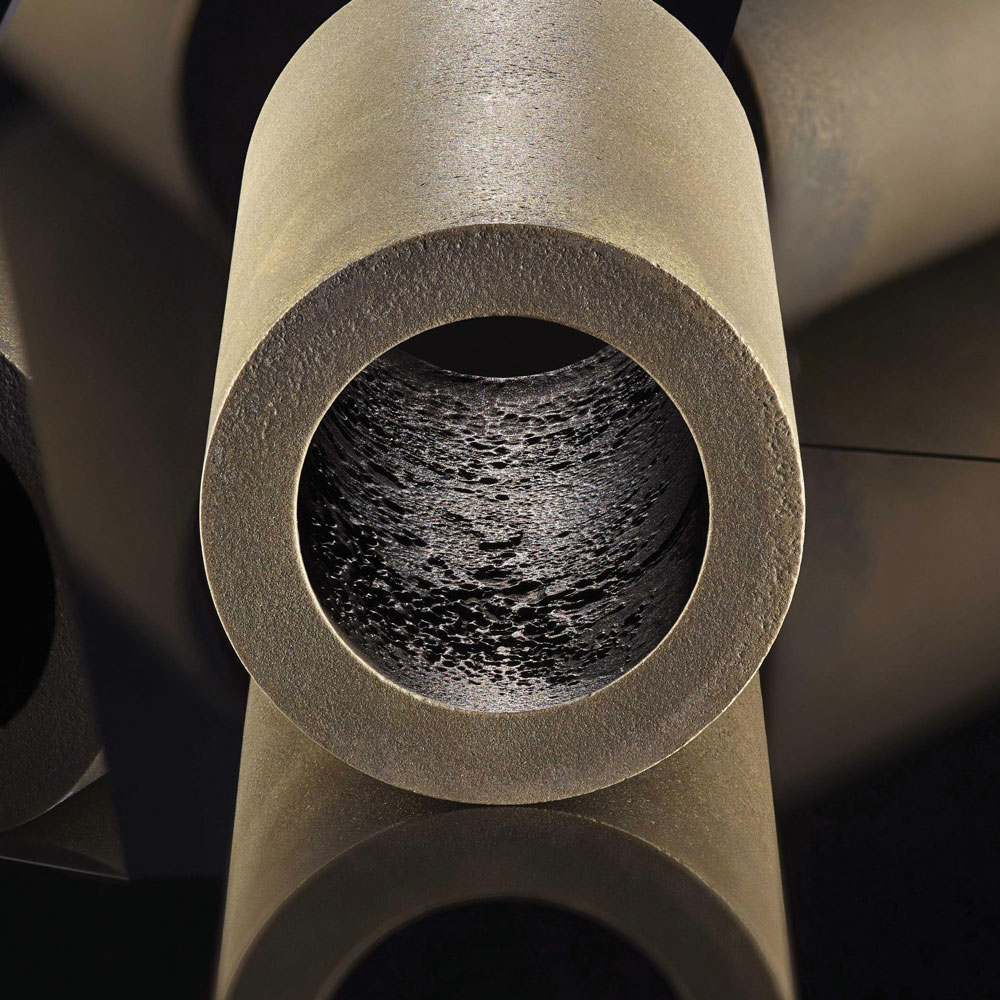

No better illustration than the Octo, a multi-faceted megalith of watch-case design. In leaning into this as its ‘halo’, Bulgari made things particularly hard for itself: the case of the Octo is a symphony of 45-degree angles, overlapping surfaces and faceted layers, with 110 different plains, each of which has to be cut, milled and polished from a single block of metal.

Eighteen operations alone go into the milling of the Octo’s bezel – the one round bit of the watch. For the rest of it there are scores of processes enacted by bespoke, hugely expensive CNC milling machines. These turn raw blanks into mini sculptures that are then finessed with the manual deftness of violin players by a platoon of hand-polishers, sat at spinning fabric buffers. With multitudes of facets and angles to approach separately, the cases are coated in red lacquer, meaning that any facet that’s still red has yet to be worked on. Working to microns-worth of interplay, this is deeply nuanced stuff. But because the Octo case is a single piece of metal, things are different from most: one mistake ruins an entire case, rather than a single component.

High pressure… but importantly without applying too much pressure.

TESTING, TESTING

Tudor has risen to the antimagnetic ‘Master’ standards of METAS.

Drive southwest down the Swiss Jura’s ‘Watch Valley’, from ‘cradle of watchmaking’ La Chaux-de-Fonds to equally sleepy Le Locle and you’ll find Tudor’s new fire-engine-red factory, in stark juxtaposition to the art nouveau surroundings.

Completed in 2021, four storeys totalling 5,500 square meters represent nothing less than the cutting edge. Cutting-edge cutting (and milling, drilling, profile-turning, etc…) thanks to the adjoining Chanel-backed ‘Kenissi Manufacture’ machining facility whirring day and night.

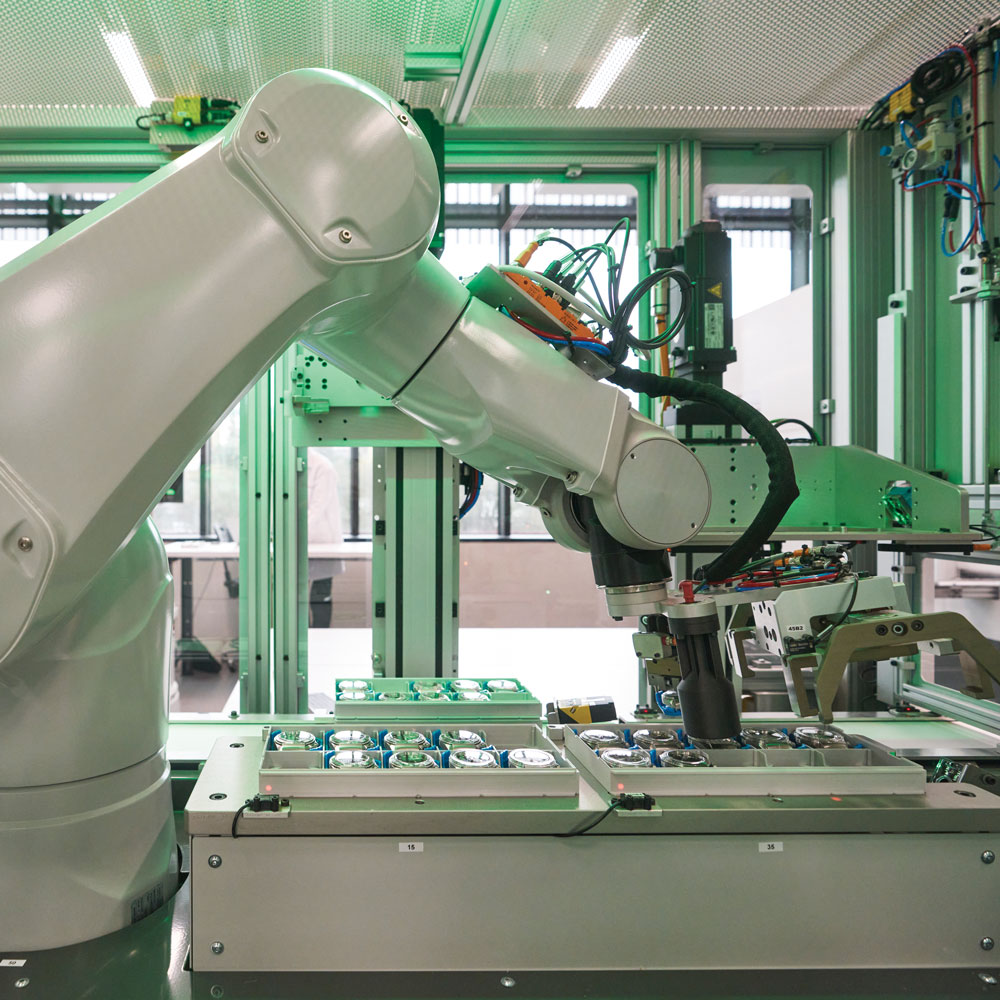

Where things get next-level cutting-edge is the assembly and quality-control department, in Tudor’s gleaming annexe, next-door. Here, the abovementioned watchmakers and their Scalextric / sushi-bar assembly lines are joined by an eerie hum…

It’s nothing short of an in-house metrology department, complete with multi-axis robotic sorting arms and actual R2-D2-like robots shuttling trays of chronometer-precise ‘watch heads’ from workbench to test bed. A programme conceived by Omega and the Swiss METAS institute metrology to be ‘open-source’, but so rigorous that it’s only been Tudor to dare to pitch its tiny metal engines against the magnets for ‘Master Chronometer’ worthiness.

Given watchmaking’s baseline ISO 764 standard demands about 60 Gauss of magnetic resistance before accuracy starts to go awry (your fridge door, or thereabouts) METAS’s 15,000 Gauss minimum goes all the way to MRI scanner-ready.

Sure enough, Tudor’s ‘MT56XX’ workhorse, complete with silicon implants, is ripe and ready for these rigours, and a new edition of Tudor’s Black Bay diving watch now beats rock-solidly to the rhythm of ‘MT5602-1U’ calibre.

That suffixed ‘U’: selected simply because of a magnet’s shape. Who said the Swiss were without a sense of humour?

CONTINUE READING

ROMAN EMPIRE

Via Condotti 10 might have been Elizabeth Taylor’s favourite stop-off while shopping the Italian capital, but recently it’s all been happening at Bulgari’s horological hothouse, over the other side of the Alps.

INKED IN, ALL OUT

Nyon’s watchmaker extraordinaire triples-down with Dalston’s tattoo artist non-pareil in an OTT reimagination of the Spirit of Big Bang.