THE ART OF LUXURY WATCHMAKING

XXth Xxxxxxxx 2018

PART I: THE UNSUNG HEROES

Step in the world of Haute Horlogerie as Alex Doak shines a spotlight on how centuries of incredible craftsmanship, outstanding feats of engineering and the countless hours spent by artisans lovingly and painstakingly creating beautiful timepieces has elevated the watch to a symbol of status and luxury.

For the first in the new Art of Luxury Watchmaking series we look back at some of the characters responsible for some of the world’s most sought after timepieces. There’s no escaping the charm of a watch.

More than just an instrument of time, a watch has the potential to leave an indelible mark in family histories. Often passed from generation to generation, a timepiece becomes interwoven into the fabric of family life, carrying with it tales that could possibly have been lost without its help.

From great, great grandfathers to the youth of today, time is quite literally of the essence for many of these beautifully crafted pieces. As such it’s little wonder that such marvels of design have a history of their own.

The captivating story of the art of luxury watchmaking has a wealth of twists, turns and fascinating subplots. However, contributions of three pioneering characters are crucial to setting the scene.

Scour the tomes of watchmaking history and you’ll alight on the name of Peter Henlein (1480–1542), a German locksmith widely regarded as the first person to produce timekeepers small enough to be portable. His watches were the size of tuna cans (with comparable elegance) and their mechanics were so agricultural as to require regular readjustment by sundial.

The well-crafted, reliable and above all desirable timepiece – the ‘proper’ pocket watches – began to hit their stride in the 17th century, their respective technologies and styles all evolving in parallel in pockets of western Europe, from Glashütte near Dresden, to Besançon in southeast France.

On British shores it was a Yorkshireman, one John Harrison (1693-1776), who proved that a precision timekeeper, rather than celestial observation, was the way forward in determining longitude at sea – establishing the humble watch as an infinitely more portable (and crucially, personal) alternative to clocks. Simply by comparing midday at sea to the time back at port per your on-board ‘chronometer,’ the difference would give you how far east or west you had sailed.

Harrison’s pioneering efforts paved the way for London’s world-leading watch industry, headed by Arnold & Son and Thomas Earnshaw. The underlying mechanical principle of mainspring, geartrain and ticking balance-wheel escapement was more-or-less shared around the world (the same system still used in today’s luxury creations).

And it was goldsmith Daniel Jeanrichard (1665-1741) who in a moment of genius was the first to formalise a division of labour, with his system of ‘établissage’ – independent workshops, a horizontal cottage industry structure, which still survives today in the folds of the Jura Mountains, right on the French border.

In fact, many of the workshops dotting the Jura were run by local dairy farmers who, come the winter snow, would round up their livestock and turn to their workshop. Come the thaw, they’d then traipse down to Geneva to sell their wares to the “établisseur” brands who assembled the components into branded watches.

THE PRINCIPLES OF THE MECHANICAL WATCH REMAINED THE SAME FOR FIVE CENTURIES UNTIL THE ADVENT OF QUARTZ TECHNOLOGY IN 1970.

These historical figures paved the way for an industry that has earned the reputation of being one of the most luxurious in the world, passing their invaluable skills to artisan watchmakers of the future.

However, just how do you manage to keep such an old and respected industry ticking? Bursting with fresh and new ideas, it is the young artisan watchmakers that play a vital role in securing the future.

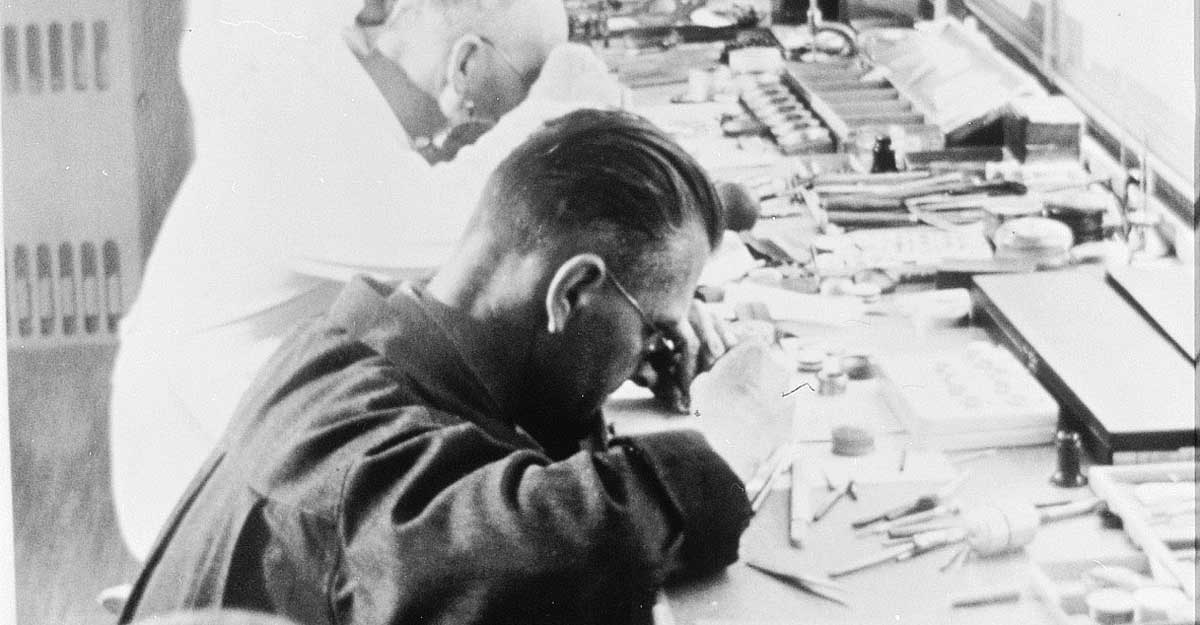

For watches to embody the art of luxury, artists blessed with the required talents must work tirelessly to craft such objects of outstanding beauty. The fruits of their labour are lauded and many of those that acquire their products are praised for their excellent taste.

While the dedication to the creation of each individual part of a watch using specialist skills is reflected in the price tag, the artisans that use traditional techniques to produce them can be less celebrated. Those that have dedicated their lives to mastering their craft are often little known outside their pockets of industry in the Swiss mountains, although some of the independent manufacturers who produce timepieces or elements of them are better known.

So, just as it’s important to recognise those who paved the way for exceptional watch craftsmanship, it’s important to celebrate those currently behind the scenes. They’re not household names per se, but their work is rightly eulogised by watch collectors and aficionados.

FERNAND SIMAO

The underlying principles of crafting Richard Mille watches are to use the sharpest cutting-edge technology, three-dimensional constructions shot through with pure mechanics, and hand-finishing. The brand is at the forefront of innovation when it comes to luxury watches, as evidenced by the RM004, which took over five years to develop and eliminated the jumping of the second hand (achieved through work on the split seconds arms). There is only one watchmaker in the entire world who can make the RM008, Fernand Simao.

Fresh RM008 kits are delivered direct to Simao’s home, where he spends six to eight weeks piecing together, adjusting, taking apart again, re-assembling, re-adjusting just one kit at a time. Simao partially attributes his talents to his mental strength: “I am a former Thai kickboxing champion of France which helps, in fact. In this sport, you develop a real ability to concentrate and focus your energy with endurance. One second of lost attention can cost you a championship. With the RM008 it is the same: as the watch nears completion, it requires ever more concentration; with all those parts in a small space, one moment is all it takes to wreck it.”

MARIO CANCELLARA

Mario Cancellara is the quiet genius behind the cases of the iconic Bulagari Octo. He is based at the Roman jeweller’s case making factory in Saignelégier, deep in the Swiss Jura Mountains. Cancellara is responsible for the complex process which produces these amazing cases for the various incarnations of the Octo. The process requires days of programming the 5-axis CNC machines before the production can even begin.

All milled from a single piece of metal, the cases are an arrangement of 110 different facets interfaced by 45-degree angles, overlapping surfaces and awkward cut-aways. With eighteen operations going into the milling of of the bezel alone, they truly are a labour of love. However, for a craftsman as skilled as Cancellara they still push incredible talent to their very limits; he’s reported to have stated “When they first proposed the Finissimo I thought we may as well just go home.”

ANITA PORCHET

Anita Porchet is a Swiss artist who is widely regarded as one of the world’s preeminent enamellers. She works from her own studio in Lausanne and so far has resisted approaches from big brands looking to recruit her in favour of retaining her independence. Porchet has collaborated with some of the most luxurious brands on watches, like Fabergé, Chanel and Hermès. She was also commissioned by Patek Philippe to work on their Aube on the Lake pocket watch to celebrate their 175th anniversary.

Porchet has an incredible gift for the delicate enamel painting that is used to decorate watches and helps set them apart. She is also known to use the champlevé technique, which requires an engraving to be filled with vitreous enamel. Post firing and cooling the surface of the object must then be polished.

There’s a mental resilience required to complement the creativity that she possesses in abundance, as she previously revealed when she stated: “Enamel requires great patience. One must have a certain character to accept that after fifteen successive fires, all the work is damaged!”