DASHING CHAP

28th February 2020

Overshadowed for too long by its square-jawed cousin, the Monaco, TAG Heuer’s Autavia is re-establishing itself on pole position as the true petrolhead’s go-to instrument. Words by Alex Doak.

Jack Heuer is the octogenarian patriarch of modern-day TAG Heuer – a spry, living legend of Swiss watchmaking with a gimlet eye and many words to the wise. Which is to forget that, on taking over the family firm in 1961 and blocking its sale to US giant Bulova, things were desperate, including his callow 28-year-old self. The success and reputation of his ancestors weighed heavy, and he needed to prove himself, let alone save the company from bankruptcy.

Surprisingly, Jack’s first answer came in the form of another failure, three years prior. “In 1958, my first year at ‘Ed. Heuer & Co. SA’, I participated in two Swiss car rallies,” he recounts in his rollicking collection of memoirs, The Times of My Life. “We were doing fine until, close to the finish, I misread the dial of our Citröen’s Heuer ‘Autavia’ dashboard stopwatch, by a minute. The result was that our team came in third place instead of first.

“This error infuriated me and I realised that the dial of the Autavia was unclear, confusing and very difficult to read correctly in a speeding rally car. Back at the Heuer factory we therefore created a new stopwatch with a large central minute hand. We mounted it into a dashboard case and called it the ‘Autorallye’.”

The upshot of which was, as well as refining Heuer’s already formidable prowess in timekeeping, Jack still had the pithy ‘Autavia’ name to hand. Since 1933, it had combined the words ‘automobile’ and ‘aviation’ as a byword for cockpit precision, rivalling Breitling’s own line in dashboard instrumentation. Come the autumn of 1961, Jack decided to revive ‘Autavia’ as an all-new wristworn chronograph, fitted with a turning bezel for the very first time.

“A bezel with 60 separate one-minute divisions,” Jack explains, “would allow the wearer to set a marker for a defined interval of less than one hour: a 12-hour division would allow the time in another time zone to be displayed: and divisions of 1/100th of a minute would be useful for time study purposes.”

Heuer’s modern era (and Jack’s career) was off to a flying start. Within a single year, Autavia was joined by 1963’s purer ‘Carrera’ chronograph, borrowing its name from Mexico’s notorious Carrera Panamericana road rally (just as Porsche did a year later when it launched the 911).

“Looking back I can say that the Autavia was the first real wristwatch product I personally created for the company.”

As this year’s various 50th celebrations have reminded us, however, 1969 saw several horological milestones that rather overshadowed Autavia’s import. Not only did Omega’s Speedmaster walk on the Moon, but Seiko invented quartz, plus every watchmaker’s Holy Grail – the self-winding, or ‘automatic’ chronograph movement – was finally brought to light. Twice.

Zenith unveiled its ‘El Primero’ straight out of the traps in January, but it was Heuer and Breitling’s collaborative ‘Calibre 11’ that made it to market first. And, sadly for Autavia, Jack Heuer wanted it to debut with an all-new and high-impact product.

Named in tribute to the equally showy grand prix, the Monaco’s cobalt-blue dial was striking enough, but in addition was a world-first: a water-resistant square case. Once Steve McQueen paired a Monaco with a Heuer-branded racesuit in Le Mans (1970), the rest would be history. A history being celebrated in no uncertain terms this year, with no less than five limited-edition Monacos. Which, if we’re honest, is rather unfair on its forefather.

Autavia’s third generation, duly upgraded with Calibre 11 mechanics (complete with signature left-handed crown) switched things up massively in the looks department. It now had an ovoid cushion case – no doubt inspired by the funkadelic styles of the time – strapped via short, square lugs. While the first-gen Autavias were largely an exercise in monochrome, these new designs brought with them a range of colourful dials, including perhaps the best-known Autavia of all: reference 1163T with a white dial and bright blue highlights.

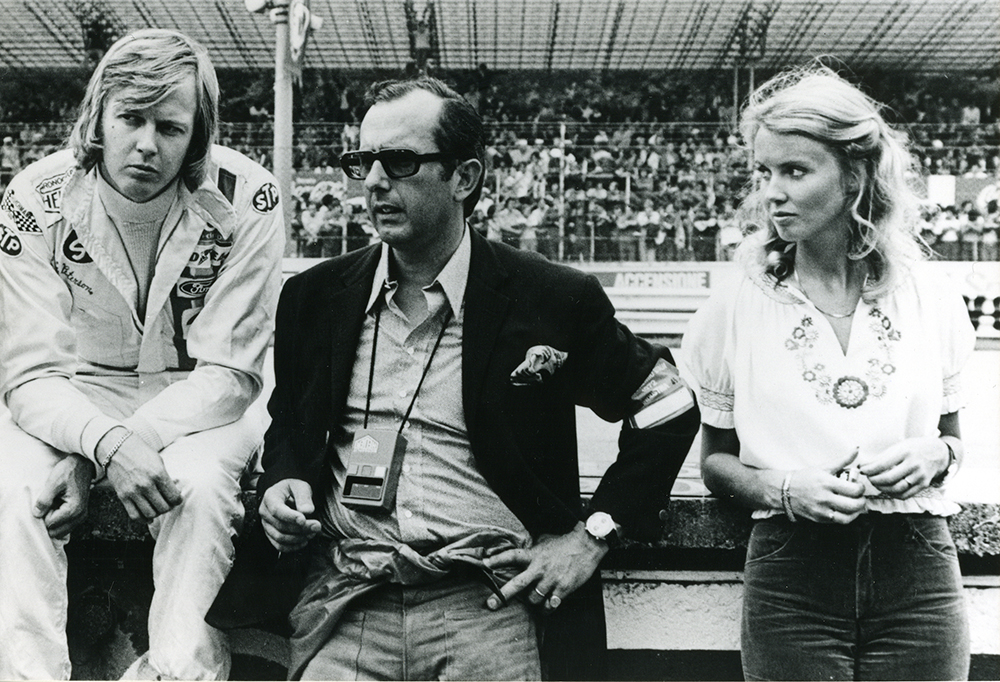

This was known as the ‘Siffert’ Autavia – and arguably it served an even more potent link between Heuer and motorsport than anything mustered by Monaco.

“I was at my golf club [in 1968] with an old friend Claude Blancpain, who ran the Cardinal brewery in Fribourg,” Jack recalls in his autobiography. “Out of the blue, Claude suggested I should sponsor a young driver called Joseph Siffert, also from Fribourg, who had shot to fame by winning the British Grand Prix that July, beating drivers such as Chris Amon, Jacky Ickx and Jackie Stewart.

“Claude considered him one of the greatest talents in Formula One racing at the time.”

A meeting was duly arranged, where Jack and Jo hit it off immediately. They agreed on the following: (1) During all races Jo would wear the Heuer logo patch on his overalls plus a Heuer chronograph, preferably the Autavia; (2) He would put a red Heuer sticker on all the cars he raced; (3) Heuer would allow him to buy its products at wholesale prices to resell them privately at races; (4) Heuer would pay him an annual fee of CHF25,000.

“Although I didn’t realise it at the time,” says Jack, “this relatively simple sponsoring contract with Siffert was probably one of the best marketing moves I ever made. It opened the door for us to the whole world of Formula One.”

Sure enough, in Jack’s words, Siffert was a born “wheeler and dealer”. He travelled everywhere with a collection of watches, which he would place with all of his friends on the circuit, somewhere between wholesale and retail prices.

“If you looked around, they all wore a Heuer Chronograph… all bought from Jo! He put it exactly in the right hands of those in his world.”

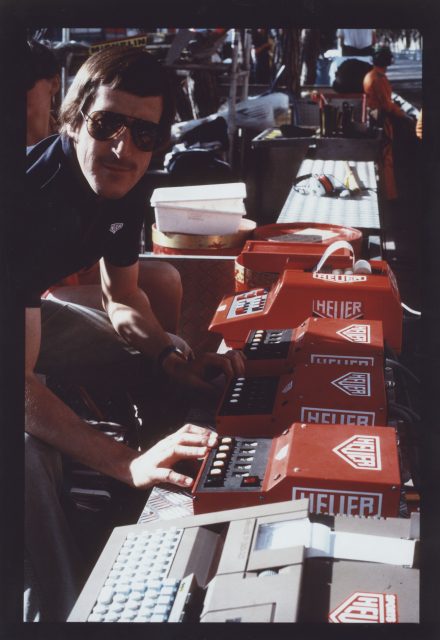

It led to Heuer’s revolutionary and long-lasting sponsorship of Ferrari’s F1 team from 1970, leveraged thanks to the watchmaker’s supply of cutting-edge digital timing equipment, which Enzo himself deemed superior to F1’s own kit. It was even Siffert’s role as muse to McQueen on the set of Le Mans that meant the King of Cool personally chose a Monaco to wear on screen. And all the while, Siffert wore his own favourite, the ovoid case with blue accents.

Today, TAG Heuer continues to burn rubber on board with Aston Martin and Red Bull Racing, as well as strapped to brand-ambassador-cum-latterday-racer Patrick ‘McDreamy’ Dempsey. And the good news for fans of Autavia’s pure formula of high-octane horology is that, while the ovoid case has reverted to its original circle (for now, at least) the choice is better than ever – both styling and performance wise.

Joining the ‘Heritage’ chronographs, this year’s time-and-date-only collection draws from Autavia’s aviation and automobile origins in the cockpit – i.e. functionality and legibility through and through. Available in steel of course, but also gritty bronze, their gradated dials in blue, black or green are each marked ‘Isograph’ and ‘chronometer’. The latter indicates that the Calibre 5 mechanics inside have been upgraded with TAG Heuer’s own silicon hairspring, which ‘breathes’ four times a second in perfect symmetry and contributes to the former’s indication of certified precision; in other words, a daily deviation of just –4/+5 seconds.

As Autavia’s first significant evolution in 50 years, it’s been a long time coming. But Mr Heuer can rest easy in the knowledge his own ‘first real wristwatch product’ is still going places, and fast.

CONTINUE READING

ROX MAN 19/20 LUXURY WATCH EDIT

The definitive directory of what you should be wearing on your wrist right now.

1969: THE DAWN OF WATCHMAKING'S MODERN AGE

Fifty years ago, to the background of Vietnam, Led Zeppelin and the Moon landings, Switzerland was undergoing its own revolution – the first spin of the chronograph’s winding rotor, to be precise.

CARBON WHIRLWIND

Since the Sixties, TAG Heuer’s chronographs have been synonymous with the world of motorsport, but never as viscerally as this year’s Carrera Calibre Heuer 02T Tourbillon.