HANDS ON

19th November 2024

At Chopard everything is done in house, including blending its own gold. We go behind the scenes to find out more. Words by Laura McCreddie-Doak.

Chopard is an interesting brand. It was founded in 1860 by Louis-Ulysse Chopard, but exudes the aura of a much younger marque, one that wears its horological knowledge lightly and uses it as much in the service of serious timepieces as it does for fun. One thing people might not know about this exceptional brand is that it creates its own gold.

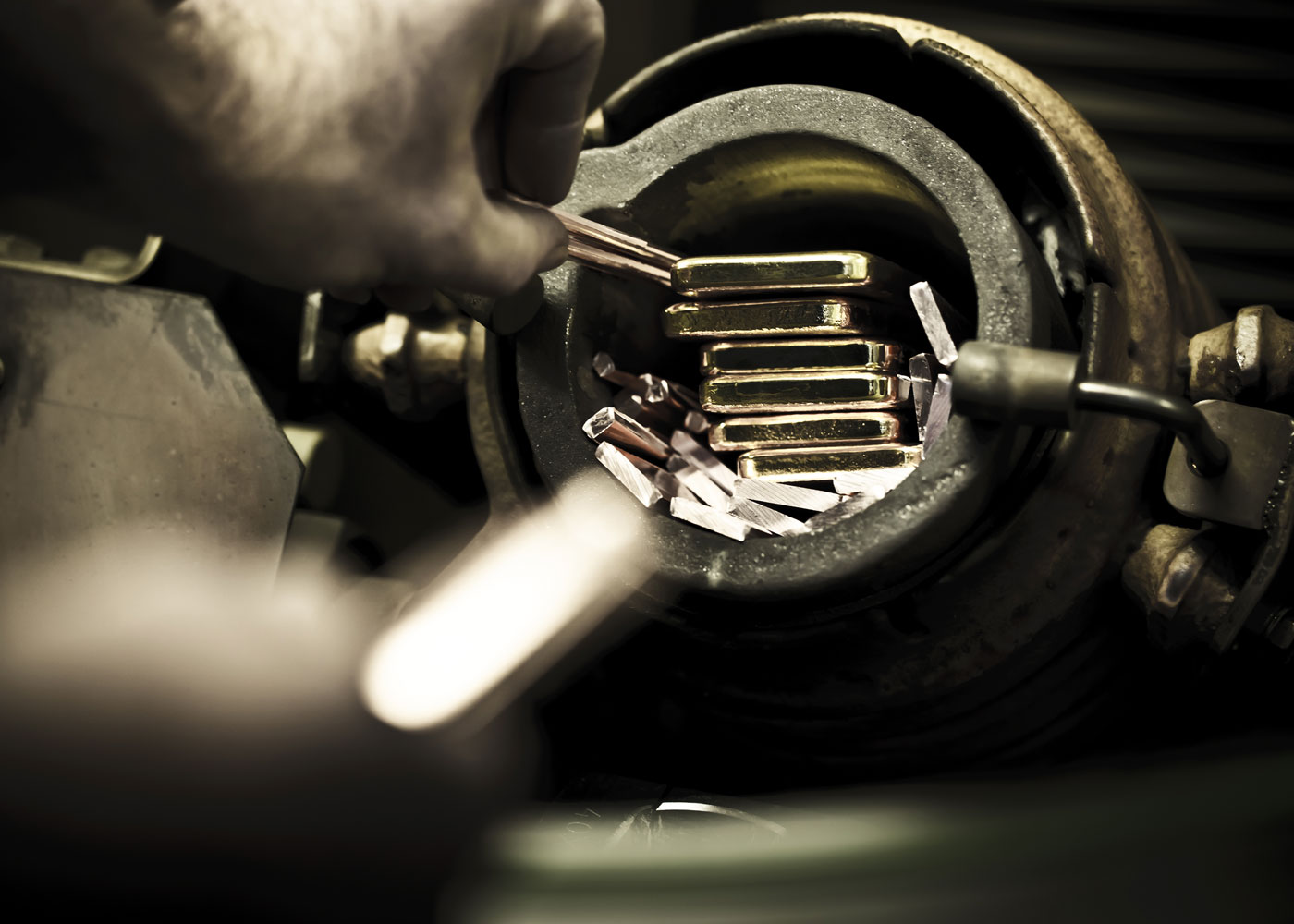

In a small, and somewhat unremarkable, room filled with machines, you’ll find Paulo. Paulo and the room he occupies domain and is, to a certain extent the heart of everything Chopard stands for. This is its foundry Chopard’s own gold is created. “Some people see me as an alchemist because I transform gold,” he says. “We produce all our own alloys, and that’s really important for Chopard. It allows us to ensure our gold is 100% ethical.”

Metals mixed by the lab next door, all sourced from artisanal and small-scale mines in Peru and Columbia, who participate in the non-for-profit Swiss Better Gold Association or Fairtrade certification schemes are poured into the furnace. The gold, whichever colour it is, yellow or pink, is melted at 1,000º, cooled in large concrete blocks. It is then rolled like pasta dough; threaded, with surprising ease, through a machine that slowly compresses the block by Paulo and his colleague over 50 times until it is at the desired width. “Some people say it is repetitive, but it depends on the person and the emotion the gold bar brings,” says Paulo. “Even though it is physical, it is something you have to love. If you don’t you can still do it, but the emotion is missing.”

It is this emphasis on care and attention, bolstered by emotion that encapsulates Chopard and the team here at its manufacture in Meyrin, just outside Geneva. The atmosphere is surprisingly convivial. In the Poinçoin de Genève workshop they huddle around microscopes admiring each other’s work or asking for advice rather than sitting in factory-style production lines. “It’s a real team effort. We help each other a lot,” grand complication artisan, Christophe, explains. “We all have different perspectives on what’s happening, and it’s important to talk so we can continually improve.” As much as the Scheufele’s these watchmakers are each other’s family.

“We produce all our own alloys, and that’s really important for Chopard. It allows us to ensure our gold is 100% ethical.”

Chopard has always been a family business. Louis-Ulysse passed his pocket watch and chronometer business to his son Paul-Louis and then grandson Paul-Andre. Having no family members to pass it on to, the Maison was bought from Paul-Andre, in 1963, by Karl Scheufele III, a German jeweller and watchmaker who was anxious to obtain a watch brand to help establish himself in Switzerland. Son and daughter Karl-Friedrich and Caroline joined in the 1980s and became co-presidents in 2001. Which brings us to Meyrin, the manufacture into which Chopard moved in 1974 and where its signature free-floating, or dancing, diamonds was conceived.

Unlike most manufactures, it is a building that feels as if it is made up of separate workshops each with its own identity and cast of characters. Upstairs from the lobby is a space where art from Karl-Friedrich’s personal collection is on display. From there it’s on to the bracelet assembly department where people single-handedly undertake every stage of the process from assembly to polishing out any imperfections. Chopard is especially proud of keeping this particular part of the process in house, using its jewellery experience and translating it into making watch bracelets. The Maison has recently upped the ante with its new, and more complicated, Alpine Eagle design meaning that having this department in house is even more valuable.

Chopard hasn’t always operated a vertical manufacture. Until 1997 it was using movements sourced from the Swatch-Group owned F.Piguet. Keen to elevate Chopard to the same horological echelons as Patek Philippe, in 1993 Karl-Friedrich set up another manufacture in Fleurier in the Val-de-Travers region of Switzerland. For a time, Michael Parmigiani was involved in making prototypes for this new venture, and current Rolex CEO Jean-Frédéric Dufour was allegedly convinced by Karl-Friedrich’s mother to quit his career in banking and help set it up. Karl-Friedrich wanted a movement that would be thin but modular so other complications could be added to it. He wanted a longer power reserve than normal, which would require two barrels, but with a small rotor so you could appreciate the beautiful finishing because, on top of all that, he wanted to be able to stamp it with the Geneva Seal or Poinçoin de Genève – a certification issued by the Canton of Geneva for exceptionally finished and decorated timepieces. For three years the new Fleurier manufacture worked this.

Unveiled in 1996 and placed in the inaugural watch of the L.U.C collection in 1997, the 1.96 put Chopard on its path to being considered a serious watchmaker and embodied Karl-Friedrich’s personal philosophy that the Maison should always strive to “add some kind of useful innovation in every movement we set out to do”. You can see this philosophy at play in the 2000’s Quattro – a four-barrel movement with a nine-day power reserve – and in the L.U.C Full Strike and Full Strike One, which uses sapphire-crystal chiming technology. Both watches contain a gong made from a single piece of sapphire crystal and are examples of how Chopard constantly strives to blend the contemporary with the traditional. This is illustrated perfectly in the synergy between the cutting-edge machinery and computers in the control centre where the watches are tested being put through precision, power reserve, water resistance, and, if they have it, chronograph running tests, and the quiet calm of the Ateliers Metiers D’art where a husband-and-wife duo, both creatively tattooed with undercuts, apply straw marquetry to dials or engrave tiny figures into cases. Julie’s particular interest is creating volume with her works of art, whereas Davide specialises more in straw marquetry and micropainting. “With a watch you usually have such little depth to work with we use different finishes such as micropainting with patina to help create depth,” she explains. This duo are responsible for such creations as the Maison’s L.U.C Full Strike Dia De Los Muertos with its grinning multi-coloured gemstone calaveras and intricately carved bezel and case made from 18kt 100% ethical gold, which brings us back to Paulo and his bars.

Maybe this is why Chopard, as a Maison, has a charm that others do not because artisan crafts and new technologies exist side by side. Most manufacture tours are cold, often impersonal experiences, where watchmakers are viewed like zoo animals through glass windows. Touring Chopard you feel the collaboration that goes into every piece. Every person is proud to be there, to be a part of these creations, from those working on haute complications to Rodeline, the polishing artisan, who started at Chopard at 15 and, in her words “really fell in love with the job” and can’t see herself doing anything else. As Paulo says “There’s a part of me in every bar [that goes into making a Chopard watch]. We’ll be gone one day, but these noble metals will be here forever.”

Chopard watches and jewellery are available online and at ROX Glasgow.

CONTINUE READING

BLINDED BY THE LIGHT

Bella Hadid has shot her first campaign as global ambassador for Chopard with a collection that started life as a watch.

RED CARPET READY

As the party season approaches, we scan the Cannes red carpet to see what lessons we can learn from the celebrities. Tip one – always wear Chopard!

ROCKS AND FROCKS

Chopard’s Caroline Scheufele took this year’s Cannes by storm with a 76-piece haute joaillerie collection and her first foray into couture.