LET'S MAKE A DATE

27th December 2018

Horology’s fabled perpetual calendar is the one complication every watchmaker wants to master – and as this year’s ultra-thin RD#2 proves, Audemars Piguet is the undisputed master. Alex Doak lifts the dial on a legacy stretching back to the days of sundials.

Over their 143-year lifetime, Audemars Piguet’s watchmakers have made a habit of responding to adversity with their best work. And that best work has always been in horological “complications” – finicky functionality on top of basic timetelling. They’ve coincided with the most challenging times that Switzerland’s finest have experienced. From 1929 to 1945, for example, fabrication of complicated watches was a tactical response to economic crisis, a way to occupy the craftsmen’s time, securing know-how for the future and working on new designs, such as elaborate openwork.

Then, the hardest hit of all: the seismic Quartz Crisis of the Seventies, unleashed by a tide of new, cheap Far Eastern technology. Instead of hunkering down and praying the storm would subside, Audemars Piguet took the long view. While the Swiss watch industry shrank to a third of its employee numbers, the Vallée de Joux’s favourite son not only continued to produce complications, but was bold enough to continue innovating in defiance of battery-powered watches, correctly predicting the mechanical watch’s eventual resurgence come the late Eighties.

AP’s fight back began in 1978 with the launch of the 2120/2800 calibre – nothing less than the world’s thinnest selfwinding perpetual calendar movement. It represented a new era of business development and growth: 7,000 movements were produced, cased and sold in 15 years. It kicked off the revival and reinvention of other classic complications, all enhanced and improved by new techniques and technology.

And 40 years on, healthier than ever, the haute horloger from the mountain village of Le Brassus is ‘perpetuating’ this legacy with the RD#2 Concept – another perpetual calendar, even thinner still at an unrivalled, wafer-thin 6.3mm. (See sidebar for how on earth they managed it.)

IT ALL BOILS DOWN TO THE HEAVENS – THE SKY BEING OUR ORIGINAL CLOCK FACE OF COURSE

The perpetual calendar has a potency that will always fresh and vital in watchmaking. Not only is its traditional four-subdial arrangement pleasingly symmetrical (not to mention especially suited to the Royal Oak’s signature octagonal frame) but its mysterious ability to tell the correct date in spite of the vagaries of our calendar – vagaries that still have the best of us muttering a rhyme every 30th of every month – exerts an elusive, romantic allure, stemming back to the dawn of time itself. A perpetual-calendar watch even takes into account leap years, thanks to a single wheel that completes a single rotation every four years.

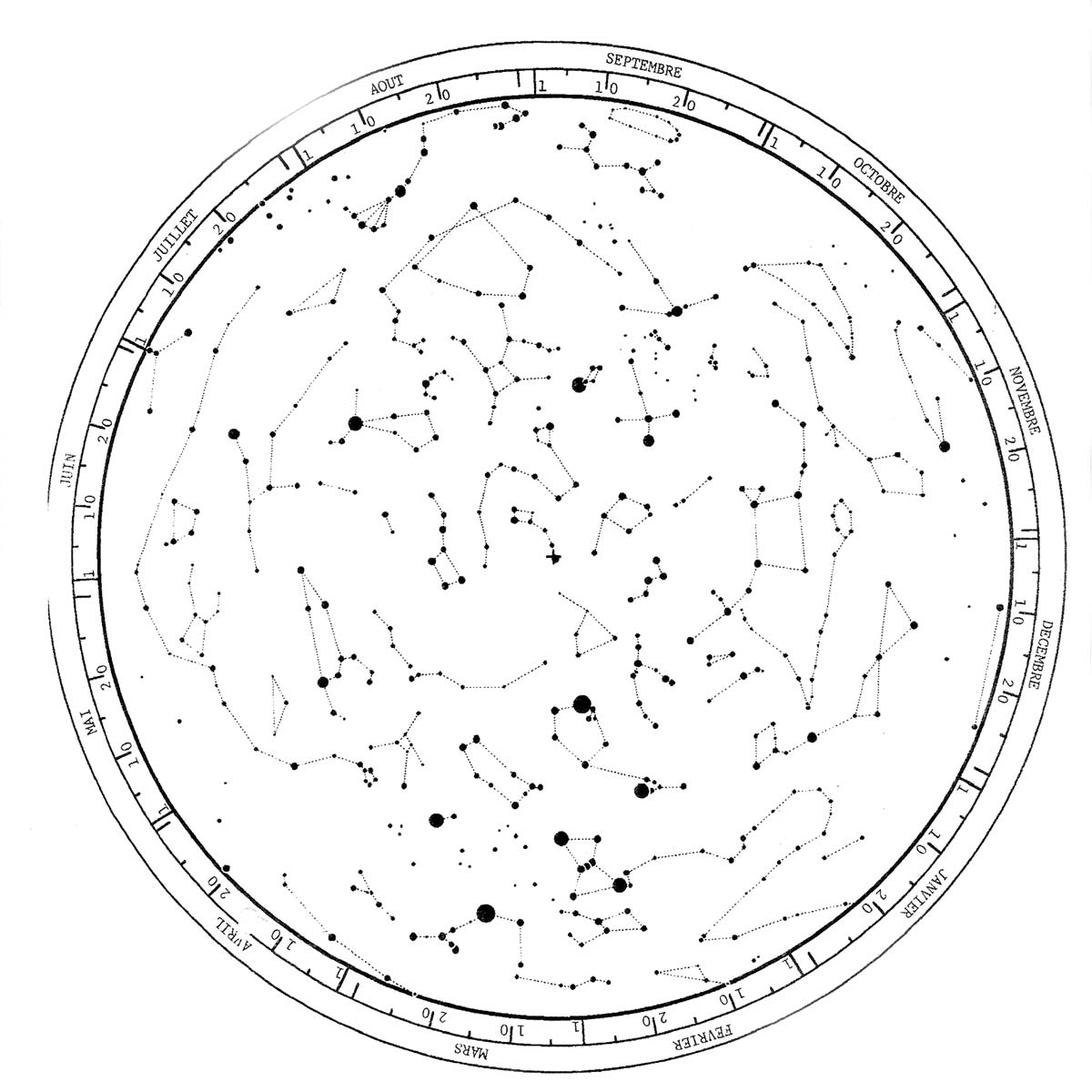

It all boils down to the heavens – the sky being our original clock face of course, and continuing to be in fact, with astronomers adjusting atomic clocks according to the occasional wobble in relation to the night sky. The sun, the phases of the moon and the observable stars were the only timekeepers that mattered for centuries, from civilization to civilization, so it was only inevitable that watches from the mid-16th century began to feature astronomical complications, including day, date and phases of the moon.

Meanwhile, the western world’s calendar was going through revision and refinement. Back in 46 BC, Julius Caesar had introduced the Julian calendar which consisted of 365.25 days, 12 months and incorporated a leap day at the end of February every four years. It was a major reform of the previous Roman calendar, which was believed to be a lunar calendar.

However, the Julian calendar wasn’t perfect either, being “late” by 10 days after centuries of lagging behind nature. Pope Gregorio XIII therefore decided to introduce a new Gregorian calendar to correct this, ruthlessly scrubbing out 11 days from the calendar and leaping from October 4th 1582 to October 15th in a single day! Still in use today, the Gregorian calendar kept Caesar’s leap-year system, but one leap year was deleted every one hundred years – apart from the last years of centuries divisible by 400. Which is why 2100 and 2200 won’t be leap years and perpetual-calendar owners will need to adjust their watches manually. Sorry, guys.

Which isn’t to take from the extraordinary ingenuity behind the perpetual calendar watch – a hugely complex micro-mechanical analogue computer on the one hand, but also the one complication that continues to embody the ancient relationship between astronomical observation and horology itself.

Its development is believed to have emerged circa 1800, but the ateliers of the Vallée de Joux – the cradle of complicated Swiss watchmaking, enjoying crystalline views of the night sky – is where it truly came to life in the 19th century. During the 1910s and 1920s, Audemars Piguet toyed with cushion shapes and art deco streamlining, then managed to shrink things into wristwatch size, with 1955 seeing the very first series of perpetual calendar wristwatches in the world to feature the essential leap year indication.

Then of course, 1978’s bombshell. Conceived in secret and developed by master watchmaker Michel Rochat (referred to as “Le Mic” by friends), the groundbreaking perpetual calendar wristwatch achieved its extra-thinness (3.95 mm) by adapting Jaeger-LeCoultre’s extra-thin automatic calibre 2120 launched in 1967 – a modular basis that survives in today’s calibre 5134.

It was 1984 when the extra-thin selfwinding perpetual calendar was introduced for the first time in the Royal Oak collection, and while production of perpetual calendar wristwatches was well underway by then, Audemars Piguet continued to create avant-garde and pocket watches too. Over the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s, Audemars Piguet has introduced a dazzling variety of perpetual calendar watches with more ‘looks’ than you’d imagine, ranging from the Royal Oak and its steroidal cousin the Royal Oak Offshore, to the circular Jules Audemars and cushion-shaped Tradition.

What says more than anything however, is that despite the many faces of Audemars Piguet and its perpetual calendar, what’s ticking under the bonnet has barely changed in a century – even in the case of 2018’s RD#2, fundamentally. A surefire sign of a watchmaker that got things bang-on right from the get-go. Given the notoriously fickle nature of a “quantième perpetuelle”, the bulletproof nature of AP’s QP says everything you need to know about its other complications.

Audemars Piguet is available online and at ROX Argyll Arcade

MECHANICAL ALCHEMY

What makes AP’s perpetual calendars tick?

Calibre 5134 is the movement found in today’s “standard” Royal Oak Perpetual Calendar – the result of mounting a perpetual calendar mechanical module onto an ultra-thin base calibre, which AP calls its 2120.

Calibre 2120 was in fact developed in the 1960s by fellow Vallée de Joux neighbour, Jaeger-LeCoultre, based on their own Calibre 960. Never used in-house, this was a blank “ébauche” movement supplied to Audemars Piguet, Vacheron Constantin and Patek Philippe. (There is a reason why people call Jaeger-LeCoultre “the watchmaker’s watchmaker”…). At Vacheron Constantin it’s called Calibre 1120, at Patek Philippe it’s Calibre 28-255, and to this day it is still the slimmest full-rotor automatic movement in production, at 2.45mm. AP afford J-LC the respect of calling the 2120 the 2120, and its perpetual calendar module is remarkably slim in itself, meaning the 5134 is just 4.31mm.

For this year’s RD#2 however, things get turned up to 11. Or down, rather down by one, as the 5134 has been modified into Calibre 5133. Over its five-year gestation, AP reduced the height of the month wheel and date wheel by merging the teeth – which count off individual days or months – with the cams, which control the length of month and account for leap years. They effectively turned a three-level movement into a single-storey construction, bringing 5134’s 4.31mm all the way down to 2.89mm. Breathtakingly elegant watchmaking.