1969: THE DAWN OF WATCHMAKING'S MODERN AGE

29th May 2019

Fifty years ago, to the background of Vietnam, Led Zeppelin and the Moon landings, Switzerland was undergoing its own revolution – the first spin of the chronograph’s winding rotor, to be precise. Words by Alex Doak.

For most of us, the summer of ’69 was the year a certain Canadian rock legend bought his first real six-string. For anyone else involved in matters cultural, aeronautical, technological and horological, it was the fulcrum to a year that changed everything.

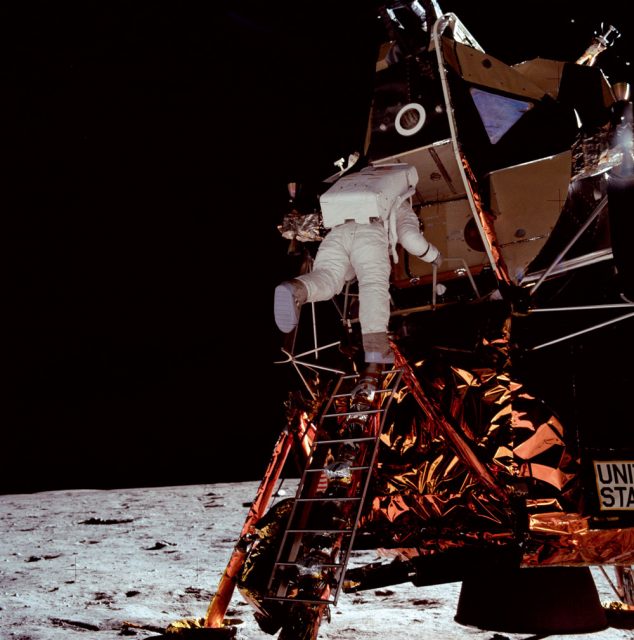

Nineteen-sixty-nine was singular in many respects. The aeronautical and space race was in full swing with Concorde and the Boeing 747 ‘Jumbo Jet’ both taking to the skies for the first time. While Bryan Adams browsed the guitar shop, the Eagle was landing on the Moon, shortly before hundreds of thousands of ‘liberated’ young people gathered in White Lake, NY, 43 miles southwest of Woodstock.

Two months after Jimi Hendrix had tortured the U.S. National Anthem with his white Stratocaster, an unintentionally portentous message was sent electronically from UCLA to Stanford Uni on the West Coast: “lo”. Actually a truncated version of “login”, it was the birth of what we now know as the internet.

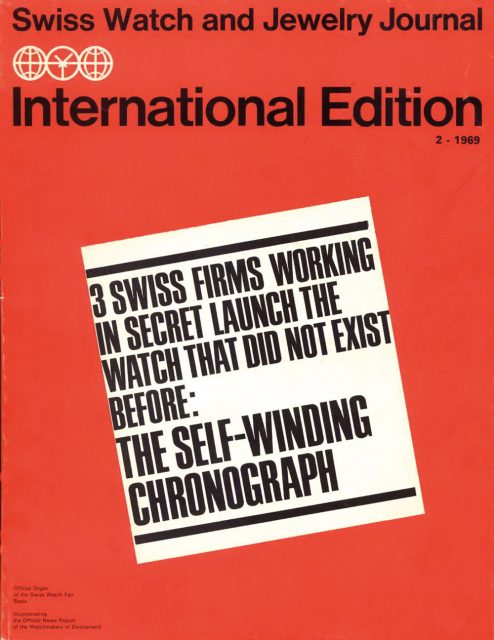

With all this going on, you’d be forgiven for turning a blind eye to the goings-on of the watchmaking ateliers dotted throughout the sleepy valleys of the Jura mountains. But for anyone sitting up in bed come the morning of January 1, 1969, groggily winding their beloved chronograph, the knowledge that not one but FIVE watch brands would finally master and market the self-winding chronograph inside of the next 365 days would seem genuinely revelatory.

It started as soon as 10 days later. Zenith held a press conference announcing its ‘El Primero’ – what was to be (in Esperanto) ‘the first’ automatic stopwatch wristwatch; nothing short of every sports watchmaker’s Holy Grail up until then. Automatic wristwatches had existed for decades, of course, but the bulk of a chronograph’s additional mechanism made the addition of a winding rotor, powered by the movement of your arm, a tight squeeze to say the least.

It was in 1962 that the basic elements of the El Primero were first consigned to the drawing board, with the intention of a 1965 launch to mark the brand’s centenary. It was to be a chronograph, the most-beloved ‘complication’ of the 1950s and 1960s, as its racy stopwatch functionality perfectly suited the breakneck pace of progress in science, technology and motorsport.

Pioneered by brands like Longines, Breitling, Omega and Heuer, the twin-pushbutton wristworn chronograph was the magic product that restored the Swiss watch industry to health after its 1930s Depression-era collapse. It was the essential accessory for the burgeoning age of piston-driven speed. But it took the jet age and golden era of F1 to push speeds way off the tachometer scale. This boom in the classic, manual-wind, ‘column-wheel’ controlled chronograph was fuelled by three Swiss movement manufacturers – Venus, Valjoux and Lémania – all of whom produced, at industrial scale, what are now considered beauteous classics of micro-engineering. (Though not as robust as Omega’s calibre 321, whose suitability means the NASA-approved watch still being shot into orbit is a manual-wind chronograph).

For most of us, the summer of ’69 was the year a certain Canadian rock legend bought his first real six-string.

But no amount of late-Sixties funkadelic case shapes, orange colour pops and Action Man advertising could detract from one thing: hand-winding a sports chronograph in that day and age was just a little… well, old-fashioned. But short of mounting a rotor on top of those three movement-makers’ already voluminous engines, what could be done? Switzerland’s boffins had been pondering this very quandary since the Fifties.

Ambitiously, Zenith’s El Primero would be ‘integrated’, meaning there was to be no additional ‘modules’ mounted on top of an existing timekeeper – whether a rotor on top of a Valjoux, or a stopwatch on top of a rotor-fitted base calibre. It was conceived as an indissoluble whole.

Furthermore, while most calibres ticked at 21,600 or 28,800 vibrations per hour (and still do) the El Primero chronograph would raise that speed to an even-more-precise 36,000. By dint of that, the accuracy of its chronographic timing was raised from an eighth to a tenth of a second. The first-ever chronograph to combine automatic winding had the extra hubris of ratcheting things up from 4Hz to 5Hz, dealing with all the friction and inertia issues in the process. Using pencils and drawing boards. And getting it so right, it’s barely been tweaked since.

The launch of the El Primero over-shot its 1965 target by some margin, eventually hitting shop windows in October of 1969, 10 months after its announcement. Which wouldn’t have mattered to head office if not for then-rival, now LVMH stablemate Heuer (now TAG Heuer).

One morning in early March, Jack Heuer announced from floor 58 of the Pan-Am Building on Park Avenue, New York the results of ‘Project 99’ – a highly secretive joint effort in cahoots with rival chronograph brand Breitling, plus movement makers Büren and Dubois-Depraz, to market their own ‘very first’ self-winding stopwatch wristwatch. Something they had brought to market come summer, pipping Zenith to the post by some months.

Arguably, it made more sense for Heuer in the first place: while Zenith was better known for its discerning chronometric pursuits, Heuer had shifted its entire catalogue’s focus onto chronographs over the course of the Sixties. Jack’s clever collusion with the playboys of the F1 pitlanes, plus his invention of the motoring chronograph as we know it (see Carrera, Autavia) meant he needed automatic technology more than anyone.

‘Calibre 11’ was the complete opposite of El Primero. Rather than being a coherently integrated movement, it was a self-winding base calibre, piggy-backed by a chronograph module. And rather than being an in-house effort, Heuer needed to collaborate with others, chiefly to get over the aforementioned bulk that would come from bolting a full-diameter rotor onto a chronograph. The kicker was Büren’s base calibre, driven by a ‘micro-rotor’, spinning unobtrusively within the volume of the other mechanics, rather than on top. Add a Dubois-Dépraz stopwatch module, Breitling’s European marketing influence on top of Heuer’s Stateside foothold, and we have three brands launching self-winding chronographs in 1969.

But didn’t we originally mention five?

For what it’s worth, American brand Hamilton ended up purchasing Büren, so they had their own dibs on Calibre 11. And history now shows that over in Japan, Seiko had beaten both Heuer and Zenith with its own 36,000vph automatic mechanical chronograph, the ‘5 Sports Speed Timer’ – dropped into domestic retailers by May. But that was the least of Switzerland’s worries, as something else was brewing in Tokyo that proved to be of far more concern to the Europeans.

Like Indiana Jones snatching his fedora as the door slid down on 1969, Seiko chose Christmas Day to launch something that didn’t just send shockwaves through the watch industry, it changed things mainstream, with a product as significant as cheap transatlantic travel, the worldwide web and free love. It was ‘Astron’ – the first-ever quartz wristwatch.

Dark clouds were about to descend on the valleys of the Jura mountains. But that’s another story altogether – and as devastating as the ensuing ‘Quartz Crisis’ would be on the traditional watchmaking craft, look where we are now. Zenith is back in rude health, pivoting about its largely unchanged El Primero since 1984. TAG Heuer has never been away, with a modern version of ‘Calibre 11’ now driving its Monaco, assuming pole position in a formidable grid of other self-winding sports timers, powered by variations on TAG’s own in-house Calibre 1887 and 1972’s Valjoux 7750 – the immortal powerhouse driving nearly every other automatic chronograph on the market, from Bell & Ross to Chopard to Bremont.

Concorde’s last flight was 16 years ago, walking on Mars is still a pipe dream, and the cool kids are shunning rock festivals for mindfulness retreats. But against all odds, 1969’s lasting legacy continues to be the self-winding chronograph.

CHILD OF ’69

For military-watch specialist Bremont, it’s quite the departure: a celebration of a civilian airliner, featuring the British brand’s first-ever (by contrast to the other two featured here) hand-wound movement. But as you’ll guess from the Supersonic’s name, it’s no ordinary airliner. This suitably streamlined, time-only dress watch in ice-white livery (from £9,495) celebrates 50 years of yet another 1969 milestone: the first test flights of Concorde. As is traditional for Bremont’s limited editions, it incorporates aluminium from the third of fourteen Aérospatiale/BAC-built aircraft, which for 27 years carried passengers 11 miles up, at twice the speed of sound. The movement features a cutely executed ‘delta-wing’ bridge, boasting eight days’ power reserve, and it comes on a leather strap in British-Airways-blue from Connolly. But if you think champagne and canapés en route to JFK pales in comparison to Bremont’s usual g-suited guise intercepting bogies, consider this: Concorde clocked up more faster-than-sound flying hours than every one of the world’s air forces combined.

CONTINUE READING

BROWSE ROX MAGAZINES SS19 ONLINE

Step into a world of Diamonds & Thrills with the latest edition of ROX Magazine.

SS19 ROX MAN EDITOR’S WELCOME

It’s my great pleasure to welcome you to another vibrant SS19 edition of ROX Man. Like last year, somewhat appropriately, I find myself writing this letter on board the annual flight to Basel, Switzerland for what – come to think of it – will be my 15th consecutive March at the watch industry’s biggest event.