IT'S COMPLICATED

22nd November 2015

Audemars Piguet’s epic split-seconds-flyback Laptimer isn’t as much of an anomaly as you might think, says Alex Doak – it’s the latest in a storied lineage of super-complications from the Vallée de Joux.

With a creak and a clatter, the dairy farmer from Le Brassus slams shut his barn door and pauses to catch his breath. It’s only October, but there’s already a sharp chill in the air, with the smudged grey clouds over the surrounding Jura peaks threatening snow earlier than usual. It’s been a rush to bring his cattle down in time for the last time this summer, but as he trudges back to his chalet in the gloaming, he’s all-too relieved. For tomorrow, he turns his hands to a very different profession – one that could prove to be his making after all. Tomorrow, as the first flakes of winter fall, our cattle farmer will sit at his workbench, remove the dustcover from his lathe, and become a watchmaker once again.

It may seem incomprehensible that a hamfisted agricultural worker could turn his hands to such delicate craftsmanship, but back then, in the middle of the 18th century, it was the only way to survive. Radiating northeastwards from Geneva, the Jura mountain range’s rolling topography makes for ideal pastures, but come the winter snow, every village and hamlet becomes cut off, leaving farmers with few means of supplementing their income; producing parts for the booming watchmaking industry of nearby Geneva.

“From the 1740s to the early 1800s,” explains Michel Golay, who runs the Audemars Piguet Museum in Le Brassus, “the watchmakers in the Joux region walked to Geneva every spring to sell the movements they’d made over the winter to the ‘cabinottiers’ and ‘établisseurs’, who finished the movements and cased them up as complete, branded watches.

“But soon enough,” he continues, “the hill farmers realised that more money could be made if they put their own names on the dials. So many of them stopped farming altogether and began making watches all year. Families throughout the valley co-operated, and gradually the quality of the craftsmanship increased, as did their reputation.”

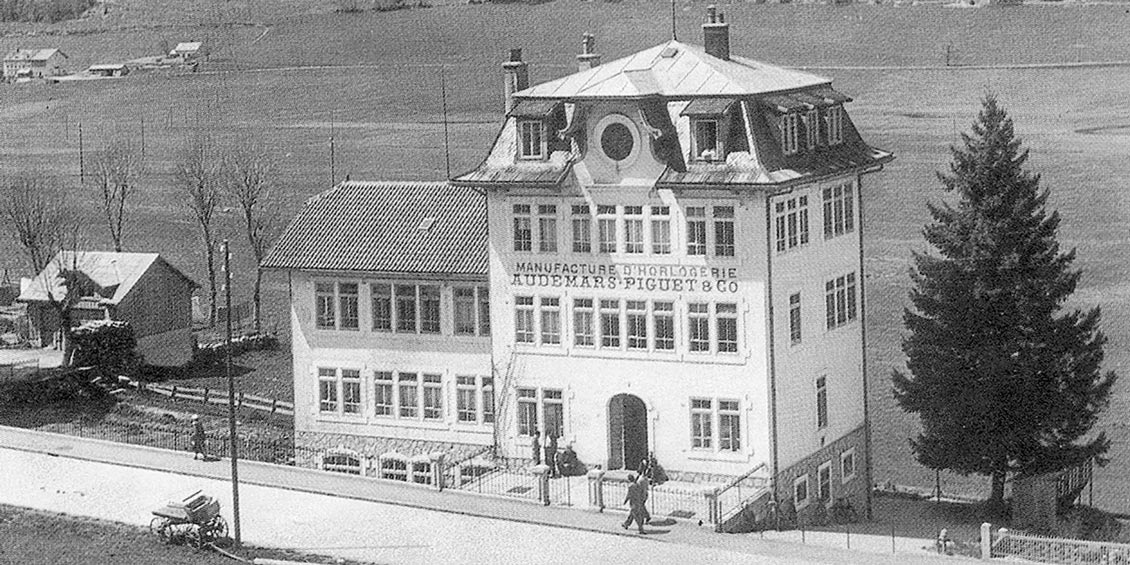

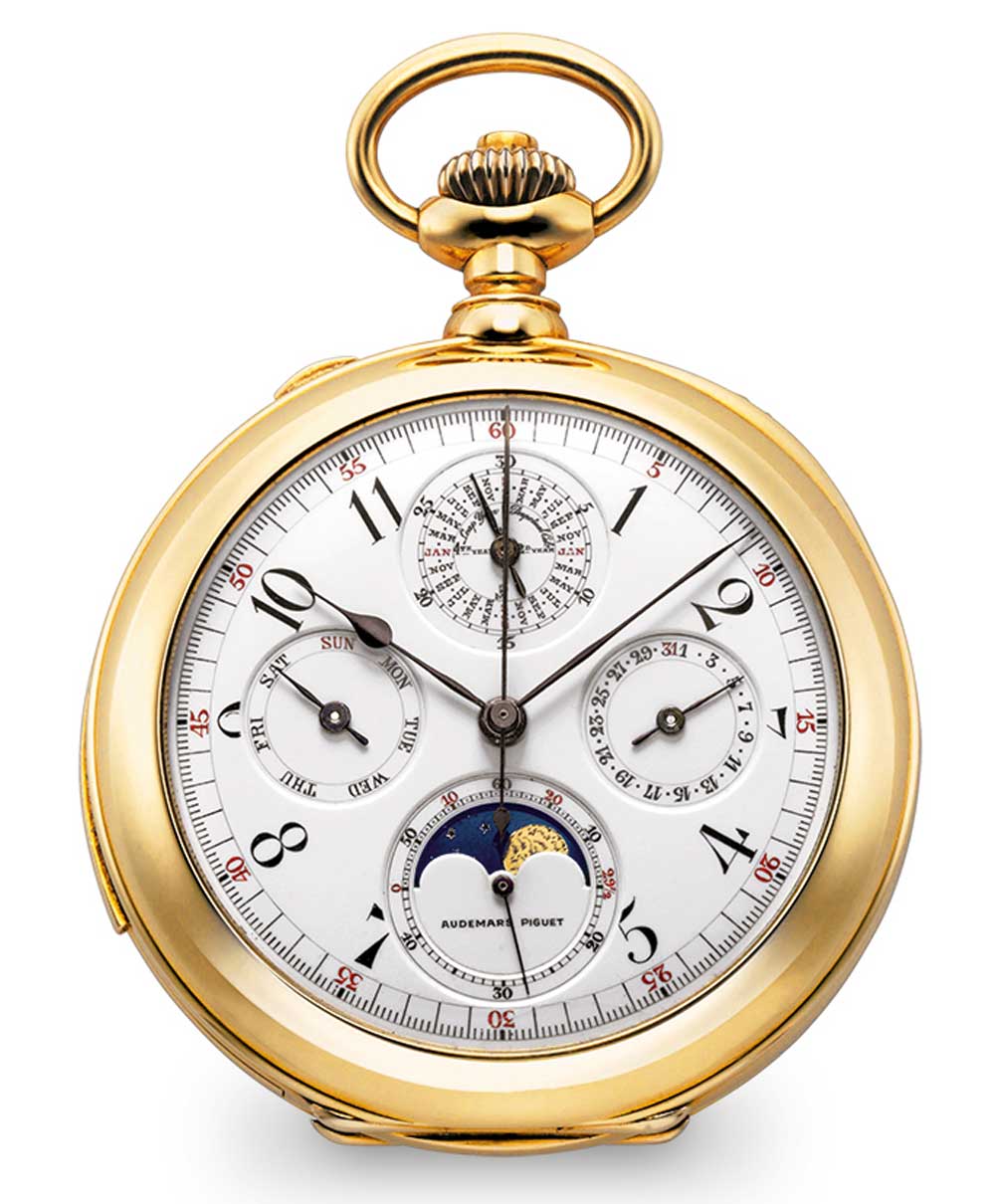

It was thus that Switzerland’s famed cottage industry – or should that be chalet industry? – arose, with brands in areas like Le Locle and La Chaux-de-Fonds especially dependent on a horizontal network of third-party parts suppliers. The Vallée de Joux, however, has always been a bit special. Rather than churning out basic calibres, it became a hotspot for “complicated” multi-functional movement making, owing to its most ancient status as a Swiss horolo-hotspot. And in the best of Swiss tradition, it still is. Both Breguet and Blancpain re-established themselves in the valley when revived by Swatch Group, taking over the venerable Lémania and Frédéric Piguet factories respectively. Jaeger-LeCoultre is still where it’s always been, on the banks of the Lac de Joux. And, of course, there’s the Vallée’s most famous resident, Audemars Piguet, whose historic museum building and newly built cutting-edge facilities are all dotted about Le Brassus. This sleepy town is more AP than town, it seems. Just as you might say that AP itself is more Royal Oak or Royal Oak Offshore than anything else. But remember that classic octagonal luxury sports watch has only been going since 1972 – before, the manufacture had always been most closely linked to the history of the “grande complication”. Still in the hands of the founding family, unlike any other Swiss maison, the Le Brassus factory is also the only one in Switzerland to have been creating grande complication timepieces since 1882, when it released a gorgeous pocket watch boasting a perpetual calendar, moonphase, split-seconds chronograph and chiming minute repeater.

Ironically, we were all reminded of AP’s complicated past in 2013 with a grande-complication version of the Royal Oak Offshore, which combined all the brand’s top-flight horological capabilities from 1882 onwards with the steroidal bulk of its modern posterboy for the very first time. Needless to say, while component manufacture has become more automated in recent history, the methods of actually assembling the Royal Oak Offshore Grande Complication’s 648 parts remain as painstakingly hands-on as in the 19th century. It will take one of the four elite watchmakers the best part of a whole year per watch. And that’s not including the 820 hours it takes another single artisan to polish and finish the skeletonised components beforehand. All in all, a mesmerising constellation of levers, bridges and pinions, working in precise harmony.

Given Audemars Piguet’s complicated pedigree, therefore, this year’s extraordinary Royal Oak Concept Laptimer shouldn’t come as a surprise. But it’s difficult not to be bowled over by the sheer, audacious design of its forged-carbon case. Nor the equally audacious horological innovation ticking beneath – a split-seconds/flyback hybrid of a chronograph that operates in a completely different way to anything before. Which, believe it or not, was dreamt up five years ago by brand ambassador Michael Schumacher. And while Audemars Piguet is far too classy to simply release a bright-red “keep fighting, Schumi” charity cash-in, the watchmaker certainly wasn’t going to let a skiing accident get in the way of horological evolution.

So many of them stopped farming altogether and began making watches all year

“He had already put so much thought and energy into this project,” attests Schumacher’s agent, Sabine Kehm, “and had been looking forward to seeing it working and presenting it to other watch lovers from the very beginning, that the idea of not completing it was never an option.” On paper, it’s an apparently simple question, which the seven-time F1 champion pitched to the Le Brassus boffins on his last visit to the factory in Switzerland: would it be possible to create a mechanical wristwatch designed specifically for motorsport, which would measure a previous lap yet carry on recording the next? To their surprise, AP’s engineers found that nothing had addressed this problem before.

A split-seconds chrono’ allows you to comparatively time a single lap by two parties. It superimposes two running-seconds hands, which you “split”, freezing one and noting its time, while the other party’s lap continues to be timed. What AP has managed – and it’s far trickier than the already-complex split-seconds – is to be able to time successive laps of a single party by pressing the button at 9 o’clock: it freezes the first hand and instantly flys the second hand back to zero to time the second lap while you note the first.

It’s a mind-meltingly complex horological operation, with a mechanism – blackened and grained for a modern, muscular finish – requiring three different column wheels, where a normal chronograph requires just one. What’s more, to ensure an exceptionally smooth operation, the watch features specially developed conical gear teeth that mesh seamlessly and accurately at all points in the movement’s cycle for perfectly linear torque transmission.

No wonder each of the 221 pieces (yes, corresponding to Schumi’s F1 career points) are priced at £175,100 each. If you can afford it though, you’ll be buying into an unrivalled lineage of complicated haute horlogerie, in its most contemporary, cutting-edge guise. Not bad for a bunch of dairy farmers, you’ll agree.

Audemars Piguet is available at ROX Argyll Arcade

DISCOVER THE FULL AUDEMARS PIGUET WATCH COLLECTION

Audemars Piguet watches are available online and in our Argyll Arcade boutique.

FROM LITTLE ACORNS

When the Scottish Open tees off this July, there will be one particular wristwatch lurking in most of the top players’ lockers back at the Gullane clubhouse. Darren Clarke, Lee Westwood, Ian Poulter and Henrik Stenson will have all de-wristed their treasured Audemars Piguet Royal Oaks before taking to the hallowed greens.

THESE CHIMING MEN

Audemars Piguet’s Supersonnerie has revolutionised the minute repeater complication, says Alex Doak – just as AP’s watchmakers have revolutionised so much of Switzerland’s sacred craft.